Tick Borne Disease Committee Updates

2024 information

Had Lyme Disease???

The Town of Chebeague Island formed an Ad hoc Committee on Tick-borne Diseases to investigate the extent of the problem on the island. We want to document as accurately as possible, the number of cases of Lyme Disease, Anaplasmosis, and Babesiosis that have been acquired on Chebeague in the past couple of years. Note that we want to hear from "you" whether or not you live on Chebeague year-round, are a seasonal resident or a visitor. If you live out of state, even if you were diagnosed in ME, your case probably has not been recorded as a Maine or Chebeague case!!

If you have been diagnosed and treated for one of these diseases, and you are reasonably sure that you got bitten on Chebeague, please share your information with us. We will document case numbers only and your name will not be shared with others.

Please contact us with the date of your illness, your contact

information, and the name of the disease/es you were treated for.

Please contact us with the date of your illness, your contact

information, and the name of the disease/es you were treated for.

Email: doublemsh@gmail.com phone: 207-846-1072

Thank you!!

Mary Holman – Chair

Steve Harris - Secretary

Anita Anderson - Island Health Officer

Cecil Amos Doughty

Leila Bisharat

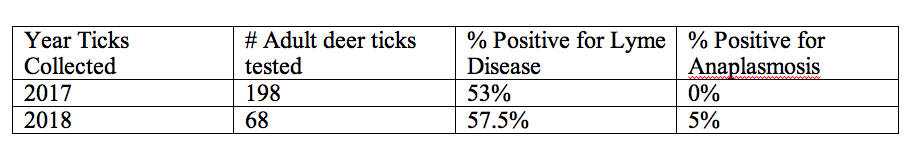

Results of the Chebeague Island Tick Surveys from MMCRI for 2018 and 2017.

Links to information about ticks:

Identifying Maine Ticks

http://www.ticksinmaine.com/ticks/deer-ticks

Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme and other Tick-borne Diseases January 2020

https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/vector-borne/lyme/documents/Lyme-Legislative-Report-2020.pdf

Report to Maine Legislature on Lyme and other Tick-borne Diseases January 2019

https://www1.maine.gov/dhhs/documents/Lyme-and-Other-Tickborne-Illnesses-Report_3-19.pdf

October 2018 Island Institute Report Fighting Ticks and Vector-borne Diseases

www.islandinstitute.org/Lyme

October 2018 Downeast Magazine article Are Ticks Changing Our Relationship to the Outdoors?

https://downeast.com/ticks-in-maine/

ME CDC Lyme Disease Page

http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/vector-

borne/lyme/

Maine Medical Center Research Institute Lyme and Vector Borne

Disease Laboratory – includes information on prevention and

landscape management.

https://www.ticksinmaine.com/

Sending a tick for identification

https://extension.umaine.edu/ticks/submit/

Federal CDC Tick-borne Diseases of the USA

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/index.html

Fed CDC Lyme Disease

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/index.html

Tickborne Diseases of the US – Reference Manual for Health

Care Providers US CDC

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/TickborneDiseases.pdf

Tick Photos

https://extension.umaine.edu/ticks/photos/

|

Below copied from the Maine Medical Research Institute - Click here to go to their website.

The “deer tick”, officially known as the black-legged tick, is essentially the sole vector of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as well as the agents of anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and deer tick virus. This tick’s life cycle requires at least two years for completion.

Following its first appearance in southern Maine in the 1980’s, this tick advanced along the coast and then inland, and may now occasionally be encountered in northern Maine. A mated adult female deer tick, having obtained a blood meal from a white-tailed deer, dog, cat, or other large mammal in the fall or early spring, may deposit up to 3000 eggs in late May and early June.

The Lyme spirochete is not passed from an infected female deer tick to her eggs. Uninfected larvae emerge in mid-summer and soon seek a blood meal, primarily from mice, other small mammals and certain songbirds. Many of the animals they feed on, particularly mice and chipmunks, will have been previously infected with the agents of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases; it is from these “reservoir hosts” that they become infected.

After over-wintering, larvae molt to nymphs which seek a second blood meal in the spring, passing on the infections they acquired as larvae to the next year’s crop of small mammal/avian hosts.

Nymphs also feed on humans, dogs, and horses, and other hosts. Their tiny size and painless bites may allow them to remain undetected through the ~36 hours it takes for spirochetes to be transmitted from a feeding tick.

Most human Lyme disease results from the bite of undiscovered nymphs in the summer. Dogs and other furred animals are more frequently infected by adult ticks which escape detection. In Maine, nymphs peak in late June and July, which is when ~65% of the human cases of Lyme disease are reported. After repletion, deer tick nymphs drop to the leaf litter, and in early fall molt to adult males and females.

2017

Dear Islander,

The 2016 Island Tick Survey is now closed. We thank the hundreds of residents who put time and effort into filling out online and paper surveys. Results will be reported before the close of 2017. We hope this and future efforts will help prevent tick-borne disease in your community.

Even though the survey is closed, we at the Vector-borne Disease Lab at Maine Medical Center always want input from the public on the issue of deer tick control.

You may reach us at the Maine Medical Center Vector-borne Disease Lab:

Summary to date (10/2016)